By Quinn Topper Marcus

In 2014, Damien Chazelle took the cinematic world by storm with his directorial debut: Whiplash, the tale of young, passionate student drummer Andrew Neiman. On paper, Whiplash is the classic teacher-student film about the discovery of self. However, Chazelle flips the classic trope, crafting a scintillating exercise in tension where the teacher is not an inspiration, but a violent, manipulative egomaniac hungry for the idea of cloning Charlie Parker, the pinnacle of jazz. It’s not just a story of Andrew coming into his own, but of the verbal and mental torture caused by his professor: Terrence Fletcher, a man who sought to mold a god out of a scrawny, awkward jazz student.

Nearly 200 years earlier, Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, a novel about a crazed, self-important scientist (Victor Frankenstein) seeking to build a creation that transcended the very laws of nature. Little did Victor know his creature would develop a mind of immense curiosity and become aware of its own existential dread and the means to which it came to be. What these two stories have in common is not just humble beginnings from both writers, but the themes involved in both tales. In both cases, Chazelle and Shelley write characters who succumb to obsession, violence, and vengeance against each other. All it takes is a spark of misguided passion.

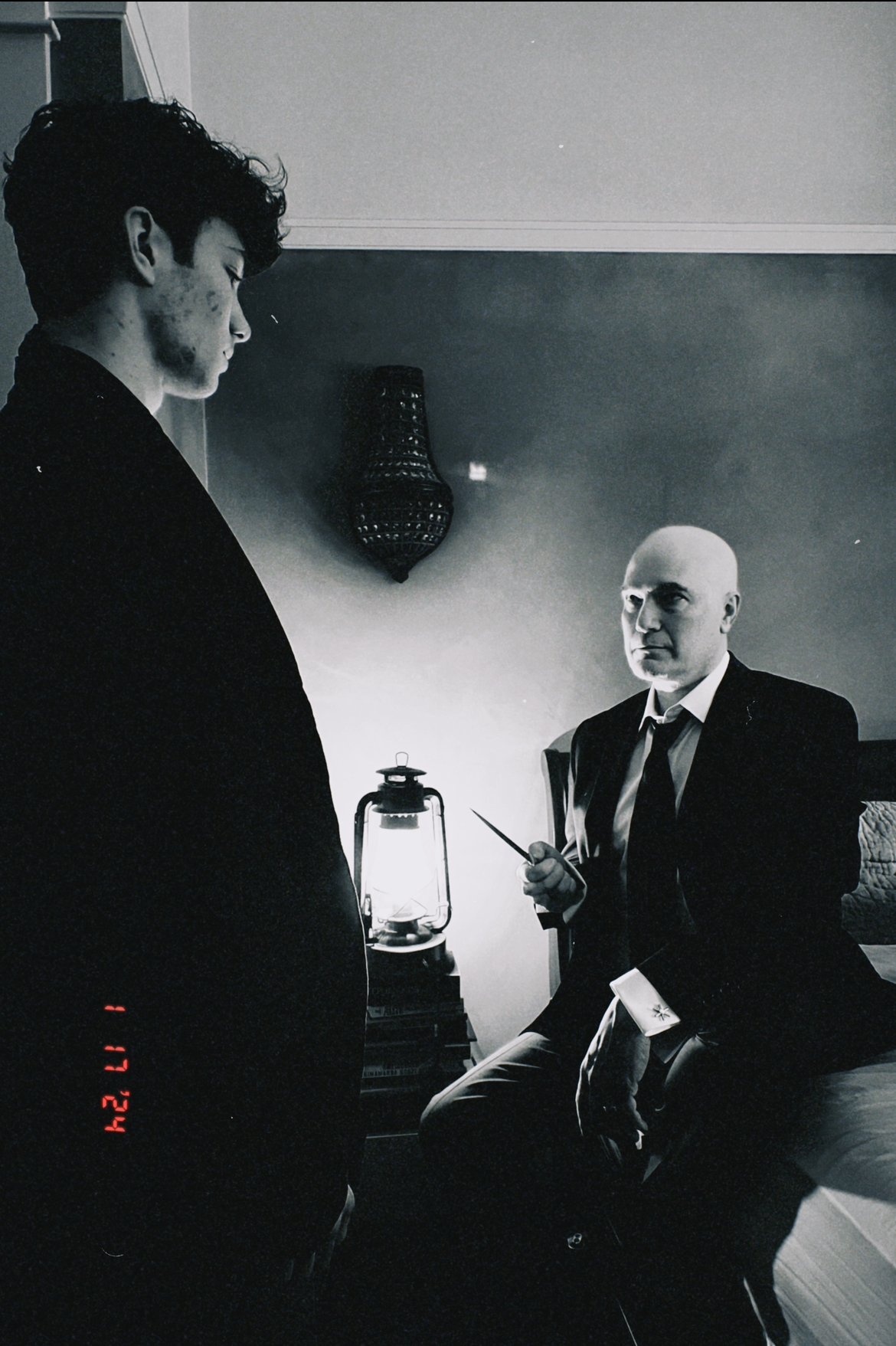

Chazelle’s Terrence Fletcher and Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein are juxtaposed to showcase malignant ambition bred from maddening passion. Victor and Terrence both have similar goals. Victor wishes to “break through” (32) the laws of the natural world while Terrence seeks to push beyond humanity’s capabilities musically. Both care very little about their ultimate creation, what they truly desire is the glory that comes with discovering such a marvel. These are two men who see the basic laws of nature as moldable. In short: Terrence and Victor believe they are gods. The obsession springs from the fact that for years, both have been tirelessly working towards their crazed ideology. Victor is self-aware of the “wreck” (32) he’s turned himself into during his two years, but allows himself to suffer in the name of his driving purpose: “a new species [that] would bless me [Victor] as its creator and source” (32). He works away in his lab, depriving himself of “rest and health” (35), closing himself off from his friends and family, and ironically finding only disgust in what he has conceived, as stated here: “I beheld the wretch–the miserable monster whom I had created” (35).

Although Terrence’s goal is not one of a scientist, his goal of training his own Charlie Parker is equally ambitious. His eagerness and undying loyalty to his cause are what connects him to Victor the most. Terrence’s tactics towards his discovery are often violent. He runs his classroom with an iron fist, cursing his students for their mistakes, and even driving one of his most “beautiful” (61) students (Sean Casey) to hang himself out of anxiety and depression. His conscious awareness of how he is affecting his own students and sheer lack of empathy is what’s most terrifying about Terrence. Similar to Victor’s reaction to his creation, Terrence has an aggression-fueled approach to his latest pupil and victim: Andrew Neiman. He threatens Andrew with violence, verbally abuses, and drives Andrew to the point of near-insanity; all for his self-important quest for musical excellence. Worst of all, Terrence advocates that he is justified in his endeavors to become the man who “made Charlie Parker” (88).

Chazelle’s Andrew Neiman and Shelley’s creature both represent wide-eyed passion misdirected into fiery rage. First, we have Victor Frankenstein’s creature, built from the body parts of the deceased; an unnatural, disproportionate horror. At least, that’s what Shelley makes us believe through Victor’s eyes. When we first meet the creature, we experience Victor’s shock, the terror he undergoes before abandoning his own creation; leaving it to wander the Earth in search of itself. The creature describes its findings as a “wide field of wonder and delight” (84). As it lives vicariously through a family he comes across, learning about language, history, and what it means to be human, we discover that the creature is a being of great curiosity and intelligence. It finds appreciation in the smallest aspects of our world: in the warmth of the sun, the sound of the birds, and in feelings it can’t quite place. The creature discovers a passion for the natural world that gives it nothing but “happiness and affection” (164).

Trouble arrives when the creature makes an attempt to socialize with this family he’s encountered and has kept himself hidden from, an act that is met with immediate violence. It’s only when the creature becomes aware of the effect it’s “hideously deformed” (85) appearance has on humans that it decides to blame it’s now torturous existence on not just humanity, but his creator: Victor. As proclaimed by the creature: “you [Victor] had endowed me with perceptions and passions and then cast me abroad an object for the scorn and horror of mankind” (pg. 100). With this new fiery rage, the creature begins its own quest, no longer of discovery, but of vengeance against the one cursed him to exist as an “unhappy wretch.”

Whiplash opens with a shot of Andrew practicing his drums, a passion fueled by determination and 13 years of practice, but one that remains more of a hobby to him than a potential career. Once Terrence Fletcher notices the slightest ounce of potential in Andrew, he pounces upon it, manipulates and pushes him, metamorphosing Andrew into the image of drumming perfection. The cost: Andrew’s well-being. At first, Fletcher’s interest in Andrew provides a newfound spark for this passion, as described here: “Andrew is stuck in place for a moment. Then, eyes wide -- is this really happening?” (18) However, once Andrew becomes immersed in Fletcher’s torture-chamber of bitter competition, his passion turns into an unhealthy infatuation. Soon enough, he breaks up with his girlfriend, claiming that drumming would get in the way of their relationship. He begins to pull away from his family, and suggests that he prefers “to feel hated and cast out. It gives me purpose” (52). A near-death experience involving a car accident on the way to a concert is what propels Andrew’s inevitable despair once Fletcher kicks him from the band. He walks into the concert covered in blood, hand broken, body bruised from the collision. This is the moment Andrew becomes his own monster. As the creature did, Andrew turns to a loathsome vengeance against his own creator, anonymously suing Fletcher for the mental abuse he inflicts upon his students. Andrew confesses to his father “he ripped me apart…” (36) and the saddest part of his early realization is that it doesn’t stop Andrew from pursuing this dark path.

The main point of contrast between Chazelle and Shelley’s characters comes towards the end, where each character learns different lessons about their misguided passions. To begin, let’s find the main points of divergence in the conclusions of Andrew and the creature. Shelley writes a miserable finale for her character, after losing his creator and not having a soul on the Earth to love him, we see the creature ready to give up. It’s a song of woe for the creature as it realizes that it no longer has a purpose on the planet now that its thirst for vengeance has been quenched by Victor’s death. So, in the presence of another man, R. Walton, the creature vows to disappear in this passage: “I shall die, and what I now feel be no longer felt. Soon these burning miseries will be extinct” (166).

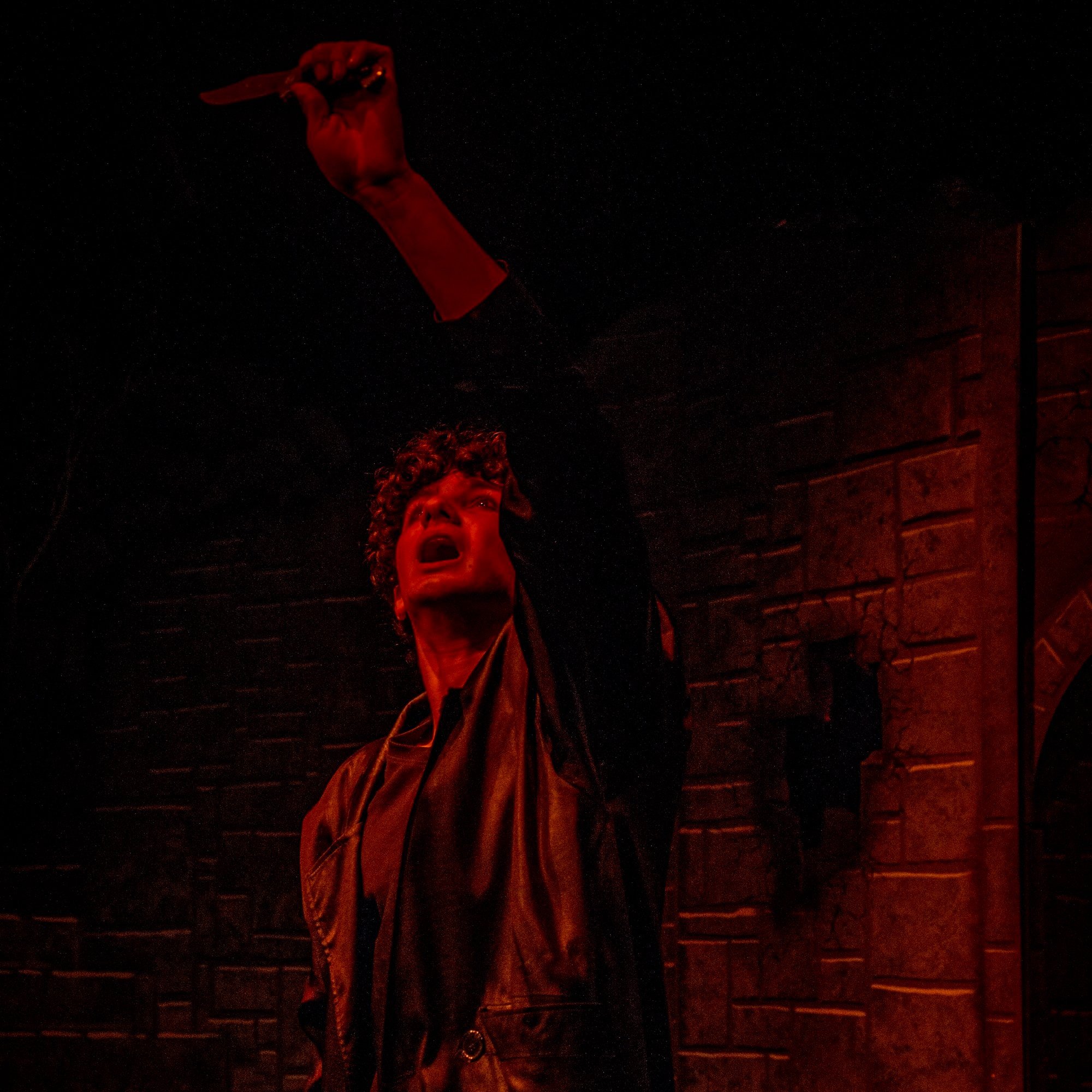

Meanwhile, Andrew undergoes a final transformation into the drummer Fletcher always wanted, a seemingly hopeful but misleading end for Andrew. At the end of the film, we see Andrew tricked by Fletcher one last time, given the wrong music for one of the most prestigious concerts in the world. After making a fool of himself and walking off stage, Andrew storms back on as a final act of vengeance against his creator, or so it seems. Andrew performs a drum solo beyond anything we’ve seen him do throughout the film, as it reads in the script: “all limbs moving in a sustained frenzy, sweat splashing, mouth open, eyes blazing, the whole set vibrating, then shaking, looks like it’s about to explode…” (102). He’s become the manifestation of perfection. He’s touched that boundary that Fletcher had been attempting for years to cross, and as they smile at each other in the final moments of the film, what’s initially viewed as a hopeful triumph for master and student collapses into a more ominous truth.

In an interview on the film’s ending, Chazelle reveals his take on where Andrew and Terrence arrive next: “Fletcher will always think he won and Andrew will be a sad, empty shell of a person and will die in his 30s of a drug overdose. I have a very dark view of where it goes.” Suddenly, the crushing weight of reality sets in, and the realization arrives that only one victor exists in Whiplash; Terrence Fletcher. After all, Fletcher is only proven correct in his methods. Sure, Andrew will likely perish in his adult life due to stress, but will Fletcher ever care, or will he be satisfied by the perfect drum solo that he taught? Andrew will always be known as Fletcher’s puppet and Fletcher will continue to bask in the spoils of creating such a player, and when Andrew is gone, he’ll move onto his next victim.

Victor meets an end not so conquering. After a treacherous pursuit of his creature, Victor finds himself aboard the ship of R. Walton, exhausted, and quickly falling ill. Here, we see Victor paying for his ambition and mistakes. In the attempt to play god, Victor loses his life. However, before the fateful moment, before his final failure of being unable to kill what he created, Victor tries to redeem himself and pass the torch to Walton. In Victor’s dying moments, his final speech is as follows: “Walton! Seek happiness in tranquility and avoid ambition, even if it be only the apparently innocent one of distinguishing yourself in science and discoveries. Yet why do I say this? I have myself been blasted in these hopes, yet another may succeed.” (162) Victor is acknowledging the nature of his failures and errors he’s made, and almost tells Walton to not fall down the same rabbit hole of obsession. Then again, the phrase “another may succeed” implies that Victor believes his quest isn’t complete and someone else must take his place in extinguishing what he swore to destroy. As Walton has been one of the only real friends to him, and he’s the only one present for his demise, Victor is subtly commanding Walton to complete what he started. One last selfish act from Victor, a man who saw so much, but was so blind to the malicious truths of his actions.

Master and slave, creator and created. The journeys of Victor and his creature, Terrence and Andrew, all intertwine to showcase the terrible effects of when one loses sense of self, replaced by an ill-intentioned purpose. Shelley and Chazelle each take their two damaged leads and create anti-heroes consumed by blind rage and vengeance towards one another. With Victor and Terrence, we observe the journey of two ambitious men, propelled by delusions of transcendence beyond what is capable of nature and humanity, disregarding their experiments in the process.

As for the experimented upon, Andrew, and the creature, what is witnessed is two lost souls with a humble curiosity for what they love. For Andrew, it’s his drums, for the creature: the world. Here Chazelle and Shelley tragically touch upon how Victor and Terrence manipulated and molded them into monsters that would soon seek to destroy their own makers. With these characters, we discover that there’s a fine line between what we consider passion and obsession, training and torture, nature and nurture. They each meet a fairly dark ending. Terrence smiles upon the success of his evil methods, Andrew achieves perfection with the price of a foreshadowed life of pain, regret, and likely premature death. The creature vows to disappear from the earth, and Victor, in his dying breath, passes the torch of his mad thirst for vengeance onto another.

They are all cursed from the beginning to the end, miserable wretches that are punished for their ways. Even Terrence, the only one affirmed for his actions, never learns from his errors, and likely never will. He’ll continue to be seldom satisfied, eternally searching for his Charlie Parker. Passion has the power to change the world, obsession is the force that brings these characters to their knees. They each flew too close to the sun and were burnt to a crisp; only ashes left behind.